HAL (HAWC Accelerated Likelihood) plugin

[1]:

import warnings

warnings.simplefilter("ignore")

import numpy as np

np.seterr(all="ignore")

[1]:

{'divide': 'warn', 'over': 'warn', 'under': 'ignore', 'invalid': 'warn'}

The High-Altitude Water Cherenkov Observatory (HAWC) is a ground-based wide-field TeV gamma-ray observatory located in Mexico, scanning about 2/3 of the northern sky every day. It is sensitive to gamma rays in the energy range from hundreds of GeV to hundreds of TeV. In addition to gamma ray-induced air showers, HAWC also detects signals from cosmic-ray induced air showers, which make up the main (and partially irreducible) background. HAWC uses a forward-folding likelihood analysis, similar to the approach that is used e.g. by many Fermi-LAT analyses. Most of HAWC’s data are only available to collaboration members. However, HAWC has released several partial-sky datasets to the public, and is committed to releasing more in the future. If you are interested in a particular HAWC dataset, you can find contact information for HAWC working group leaders on the linked webpage.

The HAL (HAWC Accelerated Likelihood) plugin for threeML is provided in a separate python package, hawc_hal. Before running this example offline, make sure that the HAL package is installed. The hawc_hal package has a few dependencies: uproot, awkward, and hist which are taken care of when you install HAL. It can be installed as follows (skip the first step if you already have threeML/astromodels installed):

conda create -y --name hal_env -c conda-forge -c threeml numpy scipy matplotlib ipython numba reproject "astromodels>=2" "threeml>=2" root

conda activate hal_env

pip install git+https://github.com/threeml/hawc_hal.git

Download

First, download the 507 day Crab dataset and instrument response file from the HAWC webpage. In case of problems with the code below, the files can be downloaded manually from https://data.hawc-observatory.org/datasets/crab_data/index.php . If the files already exist, the code won’t try to overwrite them.

[2]:

import requests

import shutil

import os

def get_hawc_file(filename, odir="./", overwrite=False):

if overwrite or not os.path.exists(odir + filename):

url = "https://data.hawc-observatory.org/datasets/crab_data/public_data/crab_2017/"

req = requests.get(url + filename, verify=False, stream=True)

req.raw.decode_content = True

with open(odir + filename, "wb") as f:

shutil.copyfileobj(req.raw, f)

return odir + filename

maptree = "HAWC_9bin_507days_crab_data.hd5"

response = "HAWC_9bin_507days_crab_response.hd5"

odir = "./"

maptree = get_hawc_file(maptree, odir)

response = get_hawc_file(response, odir)

assert os.path.exists(maptree)

assert os.path.exists(response)

Next, we need to define the region of interest (ROI) and instantiate the HAL plugin. The provided data file is a partial map covering 3˚ around the nominal position of the Crab nebula, so we need to make sure we use the same ROI (or a subset) here.

Some parameters of note:

flat_sky_pixels_size=0.1: HAWC data is provided in counts binned according to the HealPIX scheme, with NSIDE=1024. To reduce computing time, the HAL plugin performs the convolution of the model with the detector response on a rectangular grid on the plane tangent to the center of the ROI. The convolved counts are finally converted back to HealPIX for the calculation of the likelihood. The parameter flat_sky_pixel_size of the HAL class controls the size of the grid used in the

convolution with the detector response. Larger grid spacing reduced computing time, but can make the results less reliable. The grid spacing should not be significantly larger than the HealPix pixel size. Also note that model features smaller than the grid spacing may not contribute to the convolved source image. The default here is 0.1˚

hawc.set_active_measurements(1, 9): HAWC divides its data in general analysis bins, each labeled with a string. The dataset provided here uses 9 bins labeled with integers from 1 to 9 and binned according to the fraction of PMTs hit by a particular shower, which is correlated to the energy of the primary particle. See Abeysekara et al., 2017 for details about the meaning of the bins. There are two ways to set the

‘active’ bins (bins to be considered for the fit) in the HAL plugin: set_active_measurement(bin_id_min=1, bin_id_max=9) (can only be used with numerical bins) and set_active_measurement(bin_list=[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]). Additionally, you can specify the number of transits with the argument set_transits in the HAL plugin. By default, it reads the number of transits from the the maptree.

[3]:

from hawc_hal import HAL, HealpixConeROI

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from threeML import *

silence_warnings()

%matplotlib inline

from jupyterthemes import jtplot

jtplot.style(context="talk", fscale=1, ticks=True, grid=False)

set_threeML_style()

# Define the ROI.

ra_crab, dec_crab = 83.63, 22.02

data_radius = 3.0 # in degree

model_radius = 8.0 # in degree

roi = HealpixConeROI(

data_radius=data_radius, model_radius=model_radius, ra=ra_crab, dec=dec_crab

)

# Instance the plugin

hawc = HAL("HAWC", maptree, response, roi, flat_sky_pixels_size=0.1, set_transits=None)

# Use from bin 1 to bin 9

hawc.set_active_measurements(1, 9)

17:47:29 WARNING The naima package is not available. Models that depend on it will not be functions.py:43 available

WARNING The GSL library or the pygsl wrapper cannot be loaded. Models that depend on it functions.py:65 will not be available.

17:47:30 WARNING The ebltable package is not available. Models that depend on it will not be absorption.py:33 available

INFO Creating singleton for response.py:49 /home/runner/work/threeML/threeML/docs/md_docs/slow_execute/HAWC_9bin_507days_crab _response.hd5

Exploratory analysis

Next, let’s explore the HAWC data.

First, print some information about the ROI and the data:

[4]:

hawc.display()

INFO HealpixConeROI: Center (R.A., Dec) = (83.630, 22.020), data radius = healpix_cone_roi.py:87 3.000 deg, model radius: 8.000 deg

INFO Response file: response.py:554 /home/runner/work/threeML/threeML/docs/md_docs/slow_execute/HAWC_9bin_507days_cra b_response.hd5

INFO Number of dec bins: 101 response.py:555

INFO Number of energy/nHit planes per dec bin_name: 9 response.py:559

| Bin | Nside | Scheme | Obs counts | Bkg counts | obs/bkg | Pixels in ROI | Area (deg^2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1024 | RING | 450572866.0 | 4.504941e+08 | 1.000175 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

| 1 | 1 | 1024 | RING | 31550239.0 | 3.150819e+07 | 1.001335 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

| 2 | 2 | 1024 | RING | 10080669.0 | 1.005106e+07 | 1.002945 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

| 3 | 3 | 1024 | RING | 2737051.0 | 2.721557e+06 | 1.005693 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

| 4 | 4 | 1024 | RING | 346666.0 | 3.400225e+05 | 1.019538 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

| 5 | 5 | 1024 | RING | 77507.0 | 7.437867e+04 | 1.042060 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

| 6 | 6 | 1024 | RING | 14141.0 | 1.321418e+04 | 1.070139 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

| 7 | 7 | 1024 | RING | 8279.0 | 7.735450e+03 | 1.070267 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

| 8 | 8 | 1024 | RING | 2240.0 | 2.047489e+03 | 1.094023 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

| 9 | 9 | 1024 | RING | 3189.0 | 2.950479e+03 | 1.080842 | 8629 | 28.290097 |

INFO This Map Tree contains 508.195 transits in the first bin map_tree.py:156

INFO Total data size: 1.38 Mb map_tree.py:160

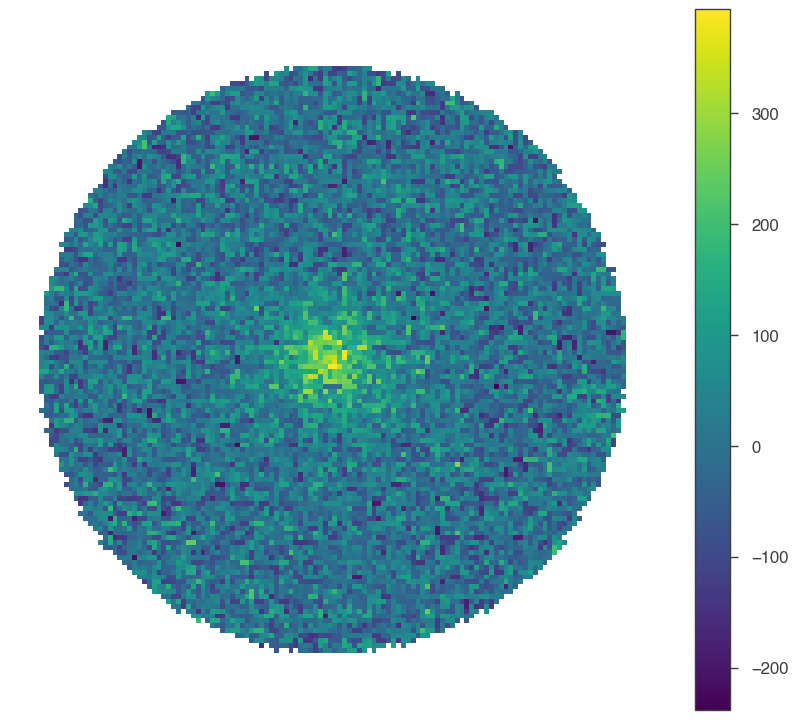

Next, some plots. We can use the display_stacked_image() function to visualize the background-subtracted counts, summed over all (active) bins. This function smoothes the counts for plotting and takes the width of the smoothing kernel as an argument. This width must be non-zero.

First, let’s see what the counts look like without (or very little) smoothing:

[5]:

fig = hawc.display_stacked_image(smoothing_kernel_sigma=0.01)

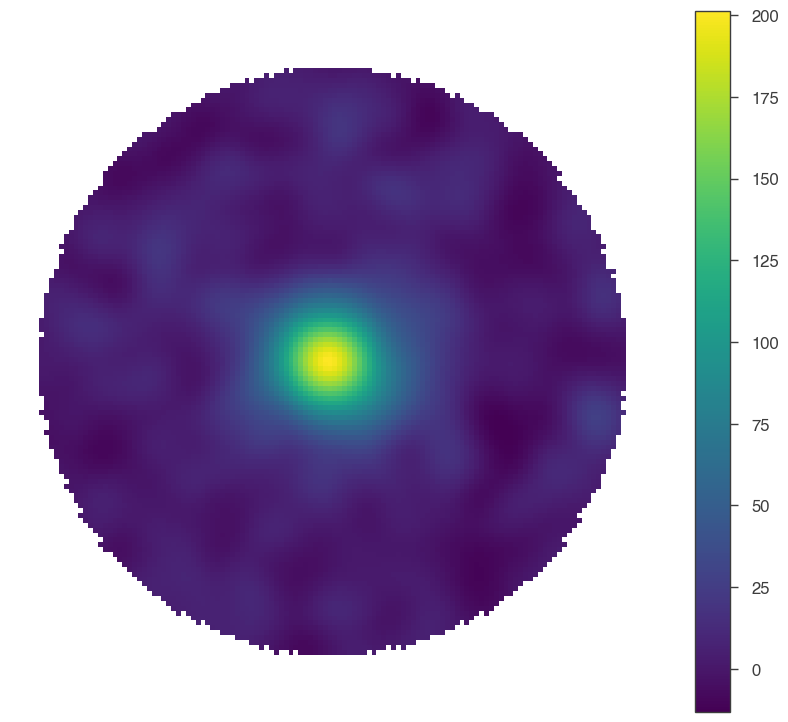

What about smoothing it with a smoothing kernel comparable to the PSF? (Note the change in the color scale!)

[6]:

fig_smooth = hawc.display_stacked_image(smoothing_kernel_sigma=0.2)

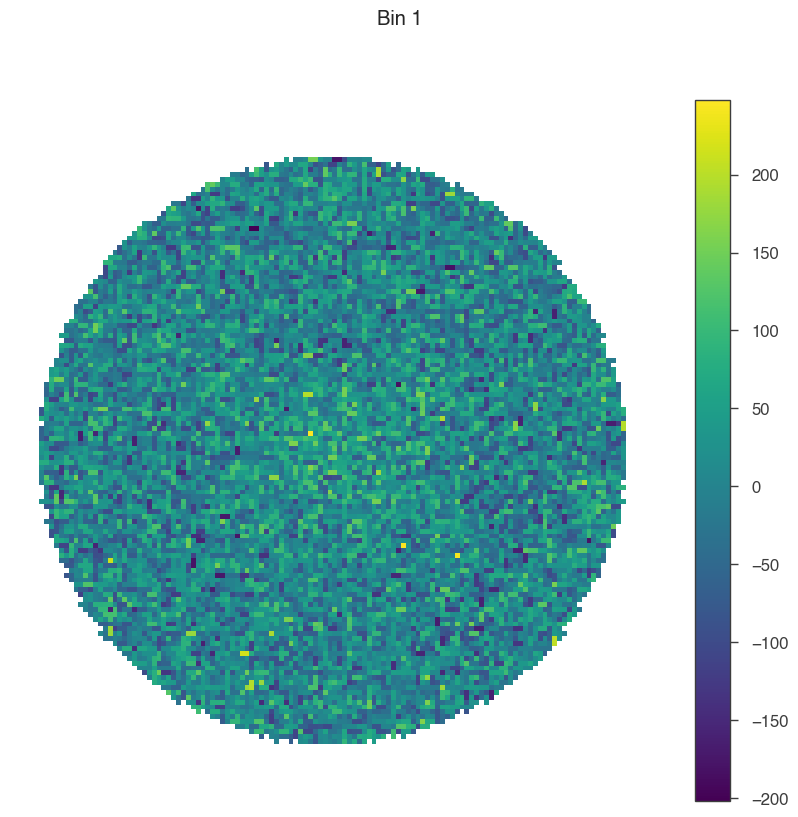

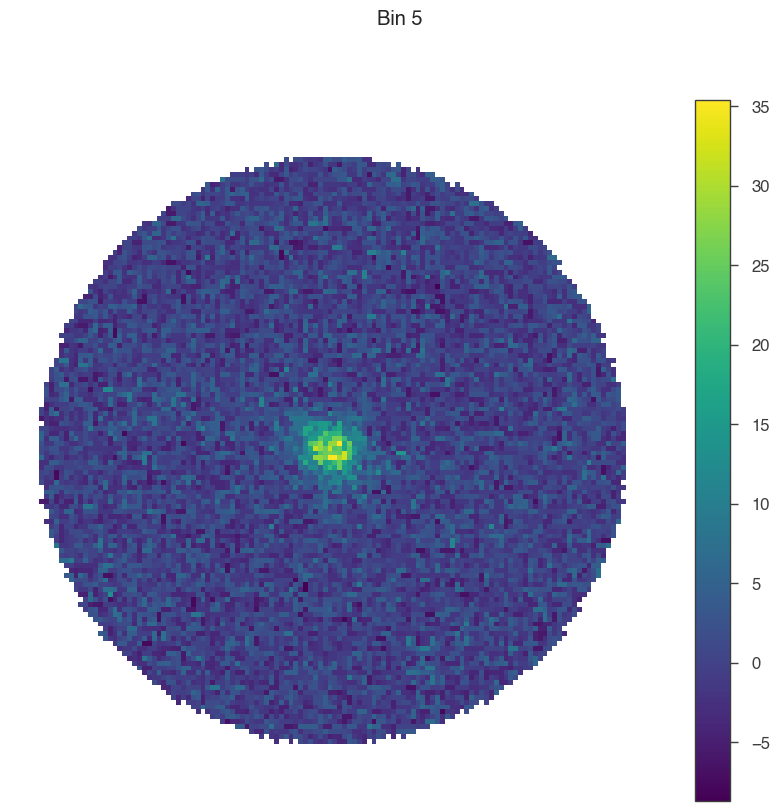

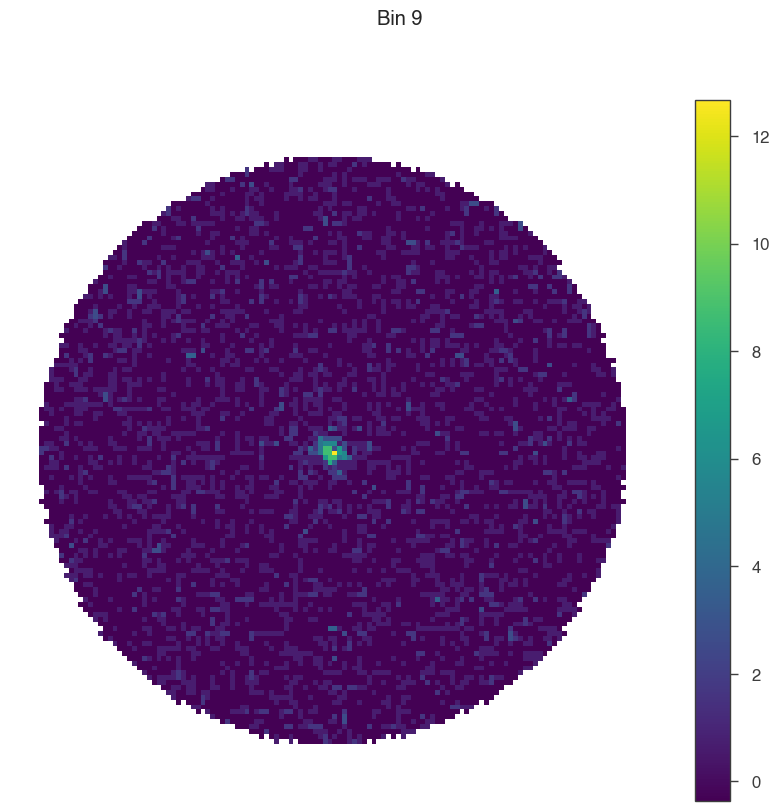

Now, let’s see how the data change from bin to bin (feel free to play around with the smoothing radius here)!

[7]:

for bin in [1, 5, 9]:

# set only one active bin

hawc.set_active_measurements(bin, bin)

fig = hawc.display_stacked_image(smoothing_kernel_sigma=0.01)

fig.suptitle(f"Bin {bin}")

Smaller bins have more events overall, but also more background, and a larger PSF.

Simple model fit

Let’s set up a simple one-source model with a log-parabolic spectrum. For now, the source position will be fixed to its nominal position.

[8]:

# Define model

spectrum = Log_parabola()

source = PointSource("crab", ra=ra_crab, dec=dec_crab, spectral_shape=spectrum)

spectrum.piv = 7 * u.TeV

spectrum.piv.fix = True

spectrum.K = 1e-14 / (u.TeV * u.cm**2 * u.s) # norm (in 1/(TeV cm2 s))

spectrum.K.bounds = (1e-35, 1e-10) / (

u.TeV * u.cm**2 * u.s

) # without units energies would be in keV

spectrum.alpha = -2.5 # log parabolic alpha (index)

spectrum.alpha.bounds = (-4.0, 2.0)

spectrum.beta = 0 # log parabolic beta (curvature)

spectrum.beta.bounds = (-1.0, 1.0)

model = Model(source)

model.display(complete=True)

| N | |

|---|---|

| Point sources | 1 |

| Extended sources | 0 |

| Particle sources | 0 |

Free parameters (3):

| value | min_value | max_value | unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.K | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | keV-1 s-1 cm-2 |

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.alpha | -2.5 | -4.0 | 2.0 | |

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.beta | 0.0 | -1.0 | 1.0 |

Fixed parameters (3):

| value | min_value | max_value | unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| crab.position.ra | 83.63 | 0.0 | 360.0 | deg |

| crab.position.dec | 22.02 | -90.0 | 90.0 | deg |

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.piv | 7000000000.0 | None | None | keV |

Properties (0):

(none)

Linked parameters (0):

(none)

Independent variables:

(none)

Linked functions (0):

(none)

Next, set up the likelihood object and run the fit. Fit results are written to disk so they can be read in again later.

[9]:

# make sure to re-set the active bins before the fit

hawc.set_active_measurements(1, 9)

data = DataList(hawc)

jl = JointLikelihood(model, data, verbose=False)

jl.set_minimizer("minuit")

param_df, like_df = jl.fit()

results = jl.results

results.write_to("crab_lp_public_results.fits", overwrite=True)

results.optimized_model.save("crab_fit.yml", overwrite=True)

17:47:42 INFO set the minimizer to minuit joint_likelihood.py:1017

INFO set the minimizer to MINUIT joint_likelihood.py:1034

Best fit values:

| result | unit | |

|---|---|---|

| parameter | ||

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.K | (2.54 +/- 0.06) x 10^-22 | 1 / (keV s cm2) |

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.alpha | -2.646 +/- 0.018 | |

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.beta | (1.04 +/- 0.14) x 10^-1 |

Correlation matrix:

| 1.00 | -0.07 | 0.82 |

| -0.07 | 1.00 | -0.39 |

| 0.82 | -0.39 | 1.00 |

Values of -log(likelihood) at the minimum:

| -log(likelihood) | |

|---|---|

| HAWC | 18765.836789 |

| total | 18765.836789 |

Values of statistical measures:

| statistical measures | |

|---|---|

| AIC | 37537.673856 |

| BIC | 37565.769985 |

Assessing the Fit Quality

HAL and threeML provide several ways to assess the quality of the provided model, both quantitatively and qualitatively.

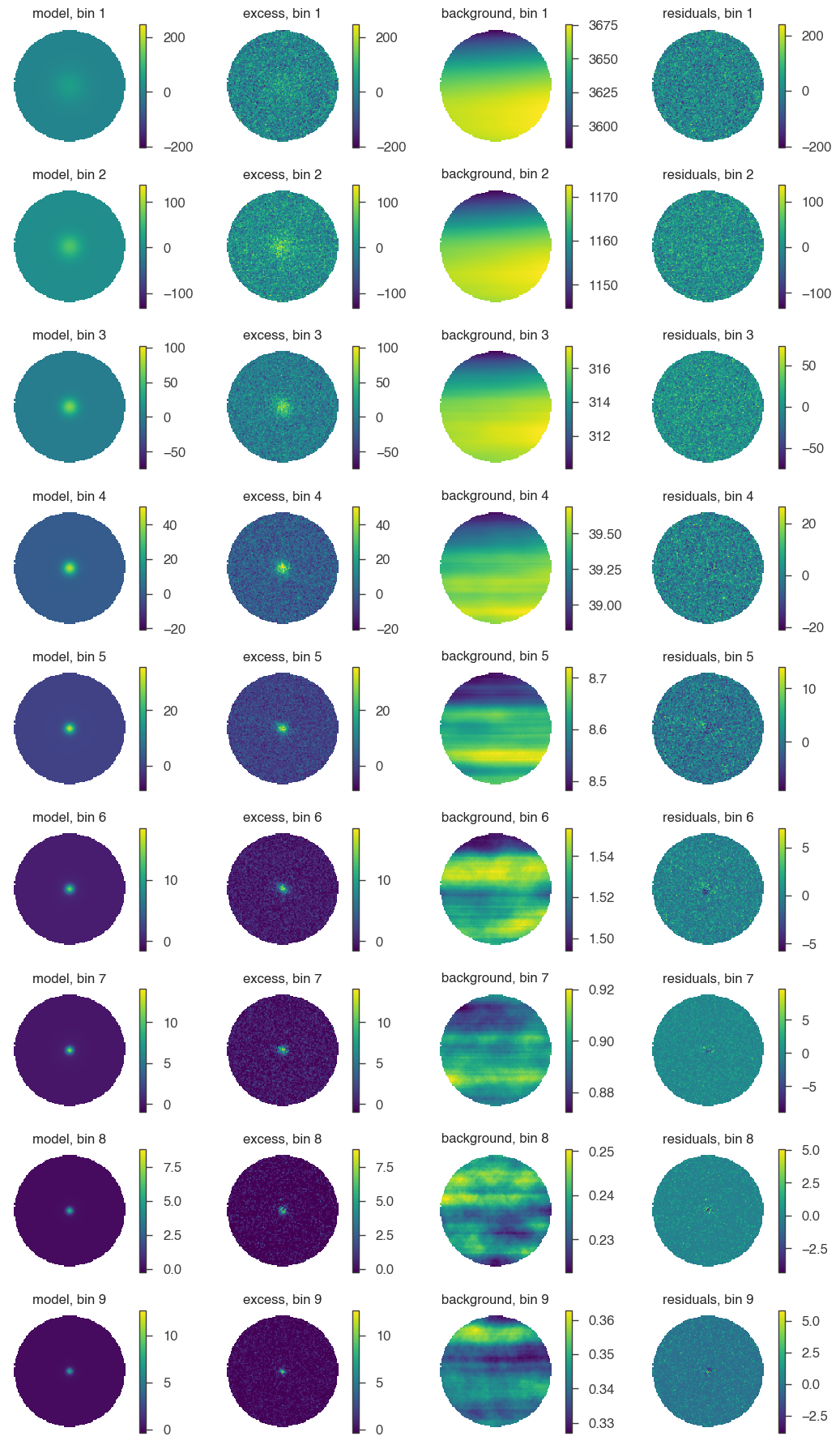

For a first visual impression, we can display the model, excess (counts - background), background, and residuals (counts - model - background) for each bin.

[10]:

fig = hawc.display_fit(smoothing_kernel_sigma=0.01, display_colorbar=True)

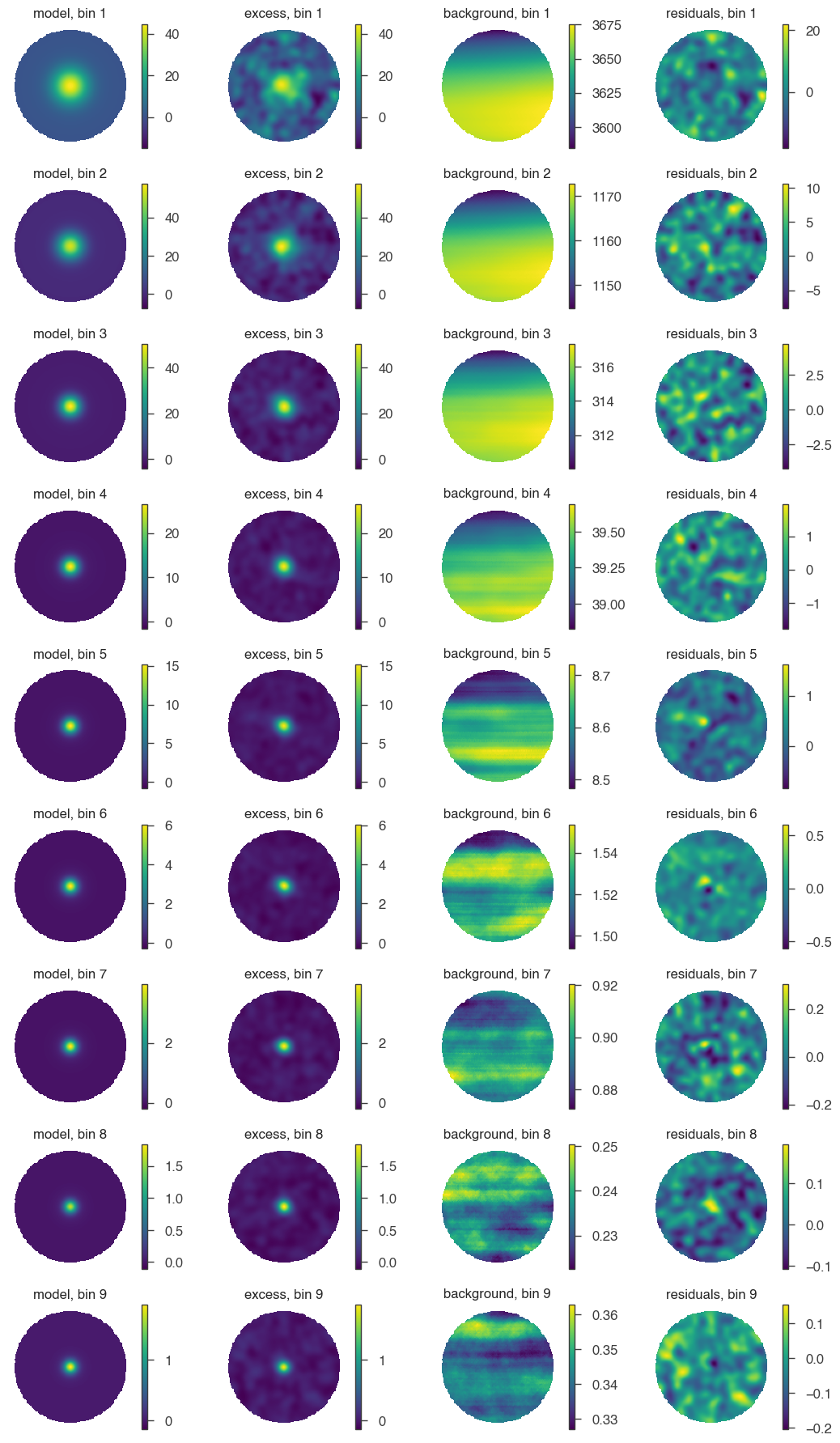

Same, but with smoothing:

[11]:

fig = hawc.display_fit(smoothing_kernel_sigma=0.2, display_colorbar=True)

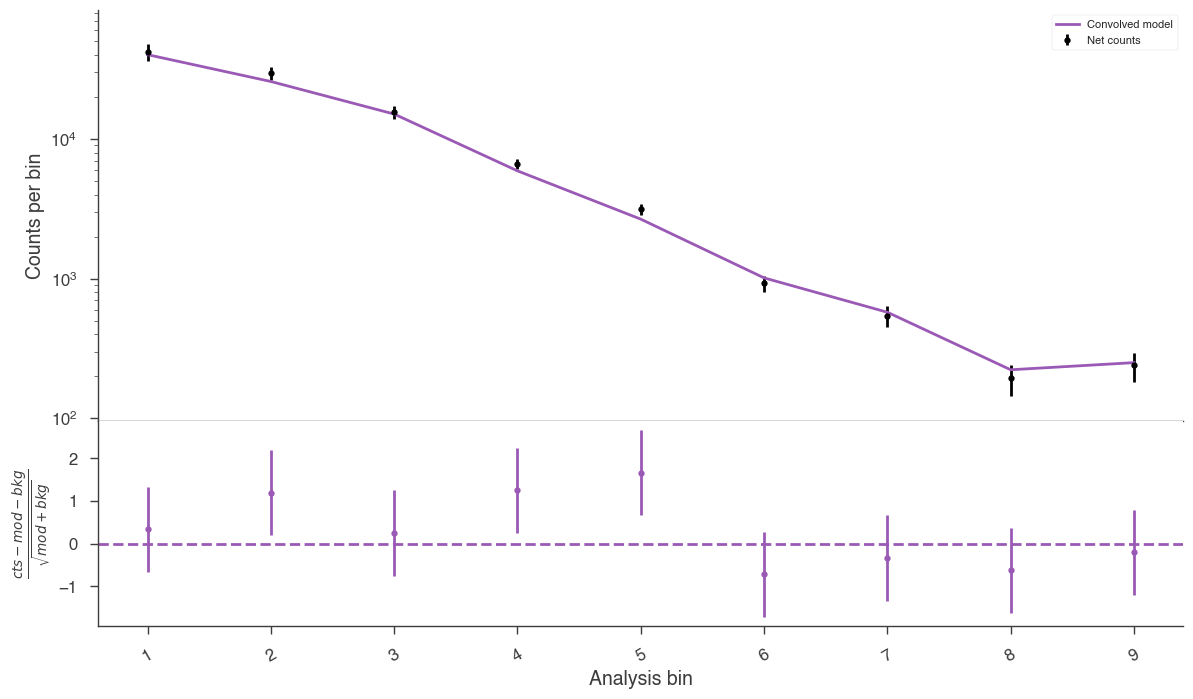

The following plot provides a summary of the images above:

[12]:

fig = hawc.display_spectrum()

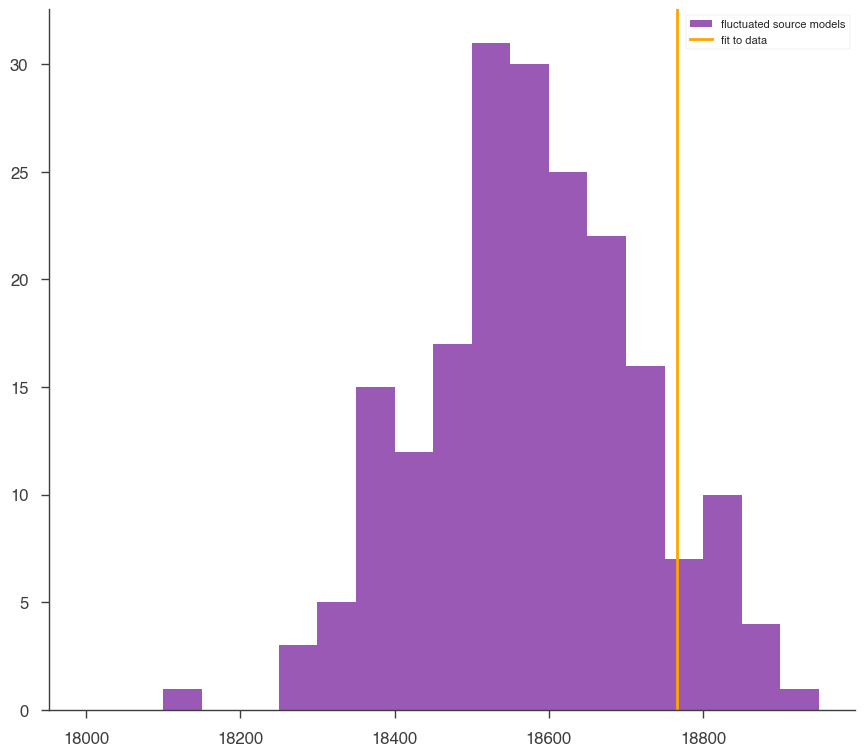

The GoodnessOfFit module provides a numerical assessment of the goodness of fit, by comparing the best-fit likelihood from the fit to likelihood values seen in “simulated” data (background + source model + pseudo-random poissonian fluctuation).

[13]:

gof_obj = GoodnessOfFit(jl)

gof, data_frame, like_data_frame = gof_obj.by_mc(n_iterations=200)

[14]:

p = gof["total"]

print("Goodness of fit (p-value:)", p)

print(f"Meaning that {100*p:.1f}% of simulations have a larger (worse) likelihood")

print(

f"and {100*(1-p):.1f}% of simulations have a smaller (better) likelihood than seen in data"

)

df = like_data_frame.reset_index()

df = df[df.level_1 == "total"]

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.hist(

df["-log(likelihood)"],

label="fluctuated source models",

bins=range(18000, 19000, 50),

)

ax.axvline(

like_df.loc["total", "-log(likelihood)"], label="fit to data", color="orange"

)

ax.xlabel = "-log(likelihood)"

ax.legend(loc="best")

Goodness of fit (p-value:) 0.105

Meaning that 10.5% of simulations have a larger (worse) likelihood

and 89.5% of simulations have a smaller (better) likelihood than seen in data

[14]:

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x7fb28ad57c50>

Not too bad, but not great 🙃. The model might be improved by freeing the position or choosing another spectral shape. However, note that the detector response file provided here is the one used in the 2017 publication, which has since been superceeded by an updated detector model (only available inside the HAWC collaboration for now). Discrepancies between the simulated and true detector response may also worsen the goodness of fit.

Visualizing the Fit Results

Now that we have satisfied ourselves that the best-fit model describes the data reasonably well, let’s look at the fit parameters. First, let’s print them again:

[15]:

param_df

[15]:

| value | negative_error | positive_error | error | unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.K | 2.540434e-22 | -6.167120e-24 | 6.514095e-24 | 6.340608e-24 | 1 / (keV s cm2) |

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.alpha | -2.645943e+00 | -1.842713e-02 | 1.770174e-02 | 1.806443e-02 | |

| crab.spectrum.main.Log_parabola.beta | 1.038787e-01 | -1.453148e-02 | 1.439298e-02 | 1.446223e-02 |

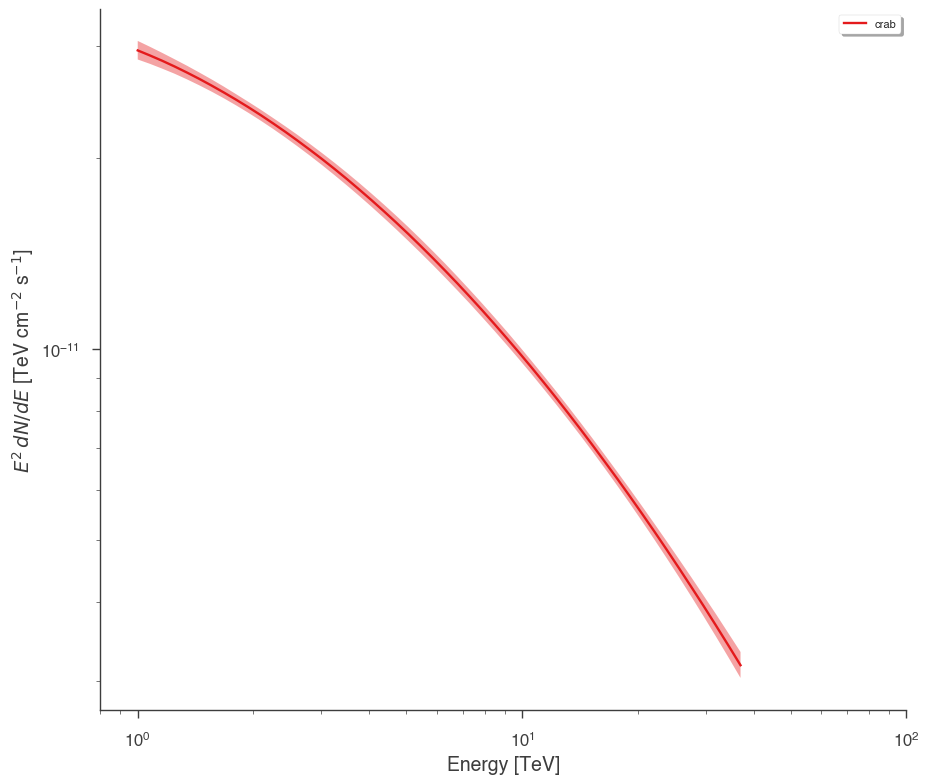

Plot the spectrum using threeML’s plot_spectra convenience function:

[16]:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

plot_spectra(

results,

ene_min=1.0,

ene_max=37,

num_ene=50,

energy_unit="TeV",

flux_unit="TeV/(s cm2)",

subplot=ax,

)

ax.set_xlim(0.8, 100)

ax.set_ylabel(r"$E^2\,dN/dE$ [TeV cm$^{-2}$ s$^{-1}$]")

ax.set_xlabel("Energy [TeV]")

[16]:

Text(0.5, 0, 'Energy [TeV]')

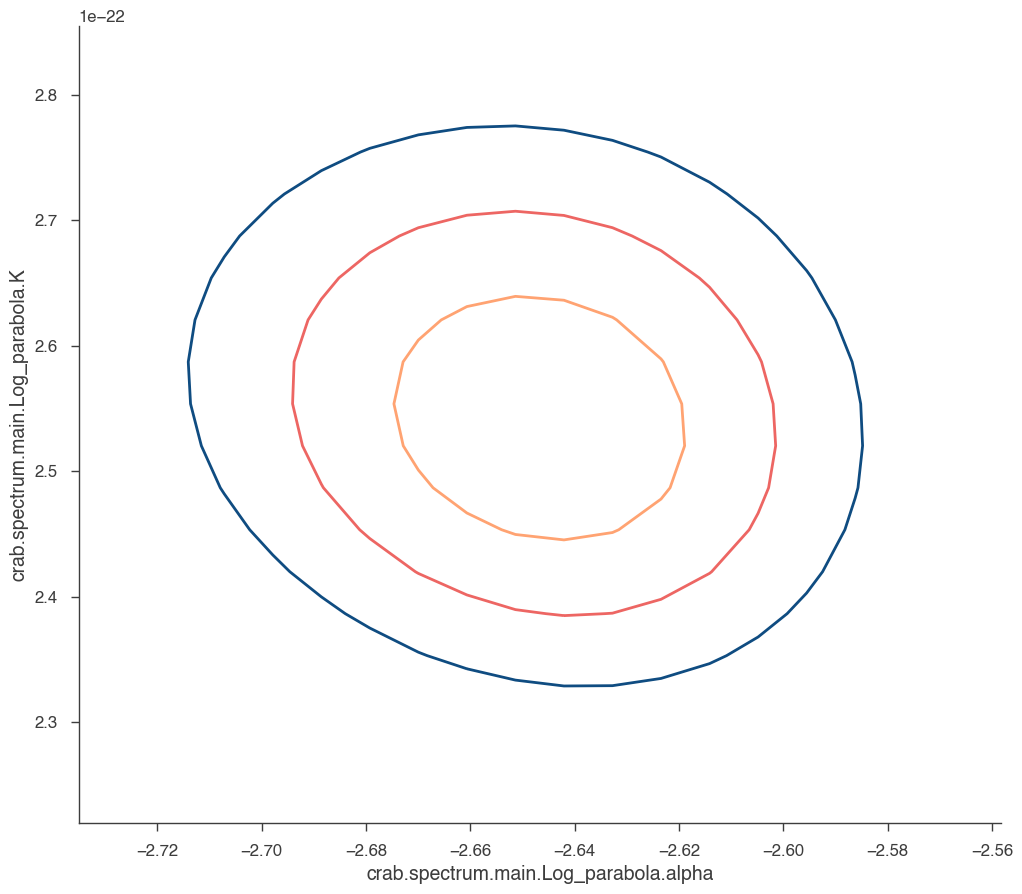

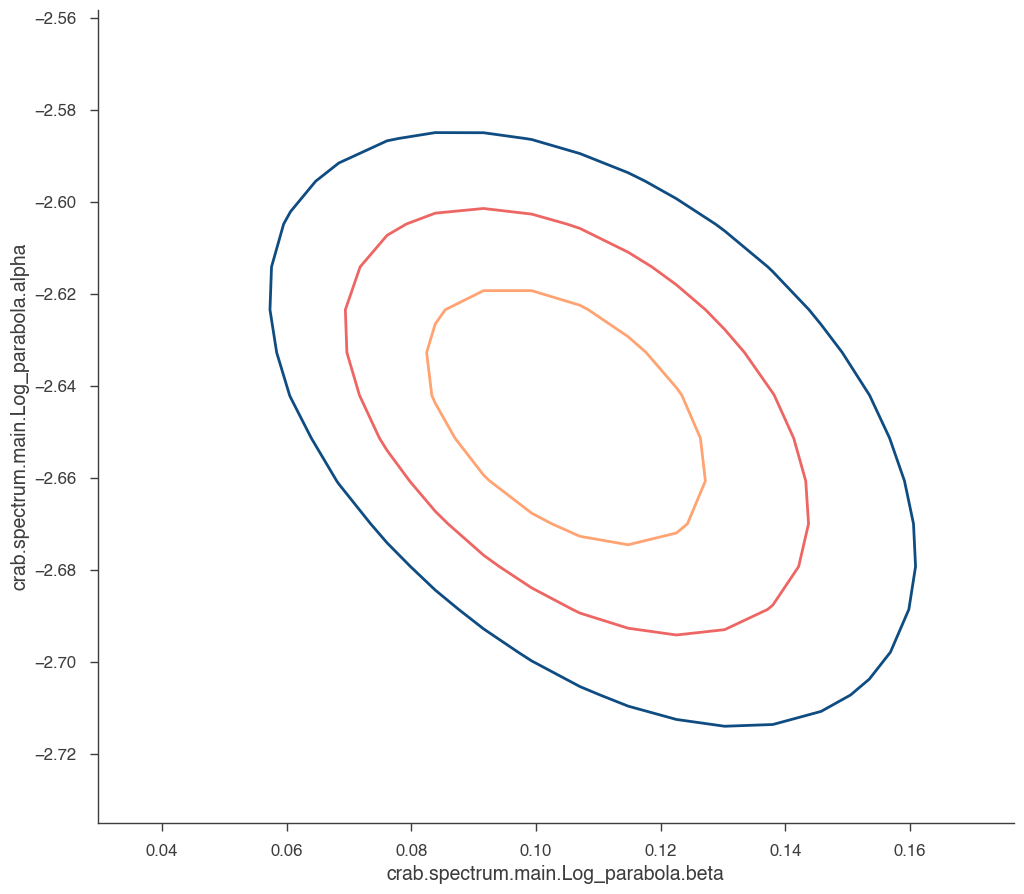

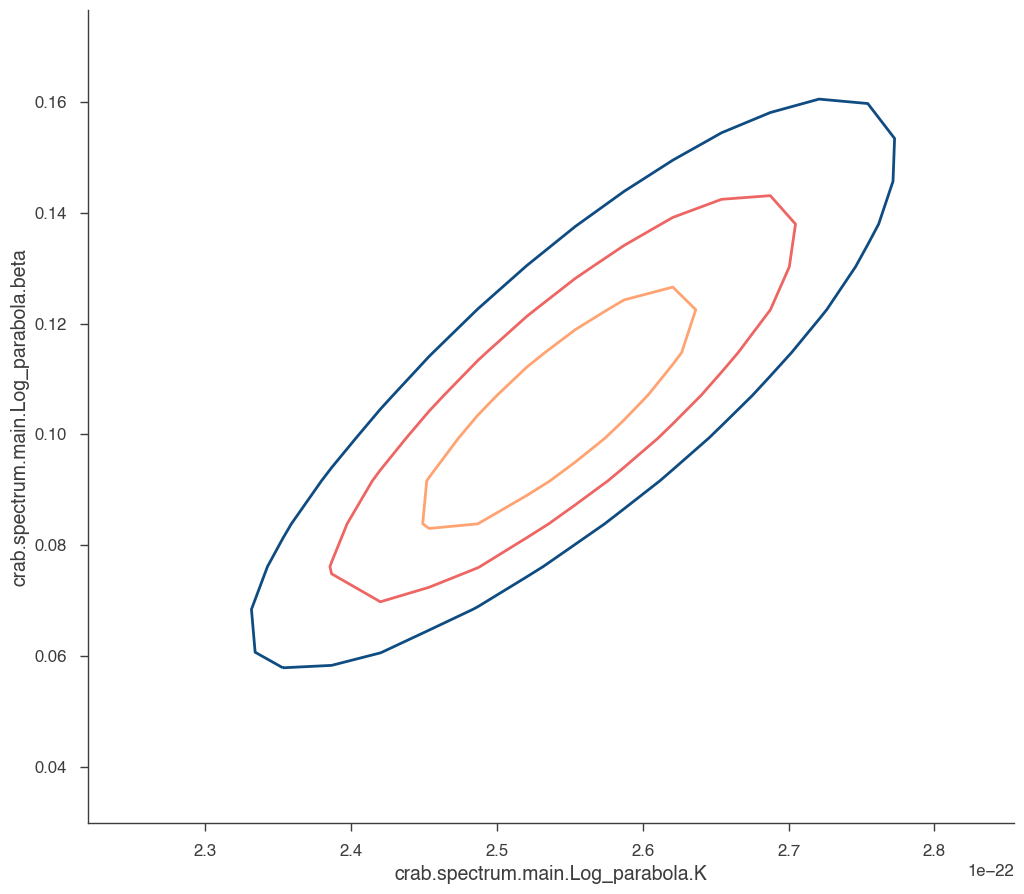

What about visualizing the fit parameter’s uncertainties and their correlations? We can use likelihood profiles for that. We need to provide the range for the contours. We can derive a reasonable range from the best-fit values and their uncertainties.

[17]:

range_min = {}

range_max = {}

params = model.free_parameters

N_param = len(model.free_parameters.keys())

for name in params:

row = param_df.loc[name]

range_min[name] = row["value"] + 5 * row["negative_error"]

range_max[name] = row["value"] + 5 * row["positive_error"]

for i in range(0, N_param):

p1 = list(params.keys())[i]

p2 = list(params.keys())[(i + 1) % N_param]

a, b, cc, fig = jl.get_contours(

p1, range_min[p1], range_max[p1], 20, p2, range_min[p2], range_max[p2], 20

)

We can see that the index and normalization are essentially uncorrelated (as the pivot energy was chosen accordingly). There is significant correlation between the spectral index and the curvature parameter though.